When you’re asked to tackle a game development project you want to have as much freedom as possible, a generous budget, long development times and a big team. That would be a dream scenario, right? …Actually, no, not really. In this article I’ll share my thoughts on why working under limitations often proves to be the best way to develop games.

Constraints Stimulate Creative Thinking

Developing a game essentially means tackling a lot of problems and challenges. As game developers we overcome the issues, addressing them with familiar solutions based on our previous experiences, on what has worked well for us in the past. Although this is a great way to get things done, having that much freedom ends up discouraging new and creative ways of solving those problems.

I think frugality drives innovation, just like other constraints do. One of the only ways to get out of a tight box is to invent your way out. – Jeff Bezos

Now, let’s examine the most constrained environment that a game developer can experience: a game jam.

Getting Out of Your Comfort Zone

A picture I took during the 2010 global game jam in Bogotá, Colombia

A game jam is all about getting out of your comfort zone and being creative. There’s a plethora of jams that you might want to participate in, such as the Global Game Jam and Ludum Dare among many others.

Generally, all game jams follow guidelines and constraints such as:

- Theme: This is always the main limitation, and is often revealed at the start of the event. All games made during the jam must be based on this theme.

- Time: You have only (say) 48 hours to create a game; this forces the team to come up with a plan and stick to it throughout the event.

- Team: Some game jams encourage people to create teams on the fly, so you will have to juggle each person’s strengths and weaknesses.

- Tools: This refers to the different types of software that might be available for participants; some game jams may focus on 2D games, some on 3D games. You will have to adapt.

These constraints force teams to rapidly prototype game designs and become familiar with limitations and scenarios found in bigger, more complex projects.

Additional Constraints

As if four constraints weren’t enough, in some game jams you can add even more to the challenge. I’m going to take as an example three of the 2011 Global Game Jam diversifiers – voluntary constraints that you can use to further experiment with new ideas and concepts.

- Automated Development: All game assets (art, sound, levels, and so on) are procedurally generated.

- Back to School, OLD School: The game must have a screen resolution of 160×144, be restricted to a color palette of four shades of the same color, and take up just 1MB or less.

- One Hit Wonder: The game can only be played once (per computer or per IP address, as appropriate).

This constraint is based around the computer art subculture demoscene which specializes in procedurally generated graphics and music. One of the best examples of a game done under this parameters is .kkrieger, a 3D game that weighs just 96k.

Screenshot from Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening

Nowadays, if I asked game developers to make an engaging game with a resolution of 160×144, some of them would think it’s impossible. Well, guess what: a whole generation of game developers managed. This constraint is based on the technical limitations of the Nintendo Game Boy.

Execution is a very small and experimental game with a very strong lesson. The game implements a interesting, out of the box idea clearly showing what constraints are all about.

When you take a look at the previous diversifiers and the games inspired by them, you can grasp how much constraints can help in creative endeavors.

Tip: Even if you’re not participating in a game jam, I encourage you to make a weekend project based on one of the Global Game Jam diversifiers as a creative exercise

What Happens Without Constraints

So far, we’ve seen the marvels of constraints, but you might be curious about the other side of the coin: what if there are no constraints when developing a game?

Well… I’ve got bad news.

Daikatana

Daikatana was a game created by John Romero, one of the co-founders of id Software (creators of the Wolfenstein, Doom and Quake series). In 1997 Romero enjoyed fame and fortune and decided it was time to make his dream game come true. He designed the game with great amounts of content in mind, more than 20 levels and plenty of weapons and monsters, with no limitations in budget, team or time. Initially he planned only seven months of development – but following multiple reschedules, changes in game engine technologies and code rewrites, the game ended up being released after three years.

Duke Nukem Forever

After the success of Duke Nukem 3D in the 90s, its creator George Broussard was ready to make a sequel called Duke Nukem Forever, it was promised to be an industry game changer but it only became the best example of vaporware.

Initially announced in April 1997, the game was expected to release a year later, but constant changes in game engine technology made Broussard change his mind multiple times while trying to develop the best looking game he could. Duke Nukem Forever ended up being released 15 years later, in 2011.

The Lesson

There are common points between the mistakes made during the development of this two games. First, both Romero and Broussard were perfectionists in a constantly changing industry, and trying to catch up with the latest in technology proved to be a fatal mistake. Second, there were no constraints whatsoever. Having this kind of freedom becomes a hindrance for game development.

The stories behind the development of this games is fascinating, if you want to read more about them I recommend the following articles: Knee Deep in a Dream – The Story of Daikatana and Learn to Let Go: How Success Killed Duke Nukem.A Glimpse at the Past, Present and Future

The foundation of the videogame industry is made of games developed in times of great limitations. The NES, an incredibly limited console by today’s standards, single handedly saved the video game industry in 1985.

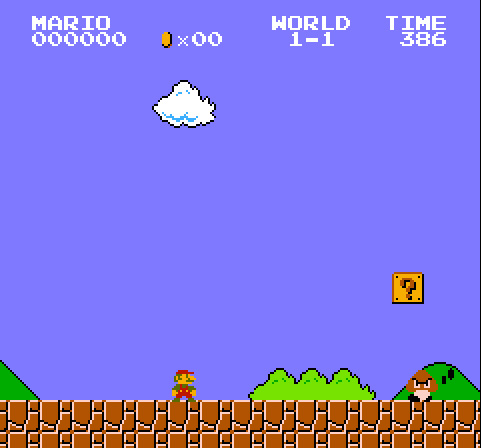

Screenshot from Super Mario Bros.

It’s a great exercise to play 8-bit games, you can get a sense of what can be accomplished using the least amount of resources. In the above screenshot of Super Mario Bros. you can see that the clouds and the bushes use the same sprite due to the NES technical limitations.

A couple of years ago, making a game independently was considered very difficult – almost impossible. Licensing a game engine was very expensive, and even if you did, it was hard to distribute the game once it was done.

Today we’re experiencing the democratization of game development technologies. With affordable (or even free) game engines like Unity, Game Maker and UDK, we have access to the same tools the AAA game industry uses, albeit with a different scope.

Having access to AAA tools doesn’t mean you should try to make the next Call of Duty, and this is exactly where independent games shine. If you’re wondering why there is a Halo 4, a Grand Theft Auto 5 and a Call of Duty 9, is because the AAA industry is afraid of taking risks; they will keep sticking to the same formulas until they cease to make money. But being an independent game developer means that you can experiment with new ideas without being afraid.

The last sequel is the one that fails to do money – Cliff Bleszinski

The future looks very bright for independent game developers. More powerful tools are becoming available at affordable prices and digital distribution channels such as Steam Greenlight are opening new and interesting paths.

Final Thoughts

Constraints can act as a catalyst for innovation, experimentation and creativity. Don’t get caught in the habit of solving problems using known methods, get out of your comfort zone and start using constraints to your advantage. Your game could be the next Minecraft…

Thanks for reading!